Words Mean Something

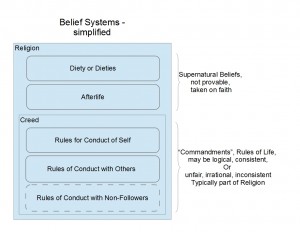

Legislators write laws. Usually they write laws after something bad happens, not before. Since ex post facto laws cannot be used to punish crimes that weren’t originally crimes, they have a preventive effect on future activities, not on what already occurred. But words have meanings at the time they’re written.

Language evolves and “must needs” isn’t part of English any more (at least in modern English), and slang is often adopted into everyday usage, like “gay” changing from “happy” to “homosexual” or some words that have taken on connotations, both positive and negative. The “Good Samaritan” was actually a sarcastic epithet, but it has evolved to just “samaritan” and connotes good behavior. “Aggression” actually meant physical force in practice, but a newer terminology of “micro-aggression” has emerged to show feelings too subtle to register as anything other than speech that someone might be offended by.

So, what exactly did legislators mean when they said “examine” or “privacy” or “secure” in their legal writings?

Only Congress Legislates

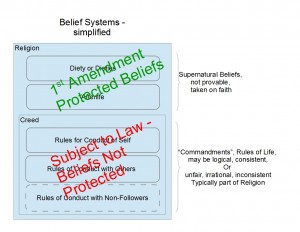

Our Constitution grants the House of Representatives and the Senate the sole power to write laws. Of course, the President is charged with implementing the laws and enforcing them, and the Supreme Court may ultimately be responsible for determining if the law was followed or not. But neither the function of Executing the law or Adjudicating the law involve “interpreting” or “extending the law via regulatory power” as you know.

NOTE: Only the House may originate spending bills, but the Senate may offer amendments (only germane ones we have learned).

These functions of “interpretation” and “extension” are truly not what was envisioned by our Founding Fathers. The Law is the law, not subject to interpretation. Regulations are not the law, but they were originally believed to fill in the blanks, gaps and details missing from the laws, as written. Now, regulators have the judicial power of “administrative law” as judges of whether the regulations are being followed. And judges can change the scope of law to make it consistent with what they believe is right, regardless of how it’s written.

These non-existent powers to interpret and extend are simply wrong.

Overlooked Provisions and Unintended Consequences

None of us is perfect. When writing a law, some things may slip by that are slightly off, or some consequences of laws may be unpalatable to particular people, especially those in the judicial system, but the cure is not to allow Executive power to usurp the Legislative function, nor to allow Judicial power to usurp Legislative function either.

The “Living” Constitution

Judges may find that a law was not violated because the law itself violates some other law or a constitutional provision, but they cannot change the law. If plants can’t be brought into a geographic area without first having been vetted by agricultural inspectors for diseases, a judge can’t say that the law applies only citizens or only to foreigners or only to certain situations when it is convenient for compliance. Judges can, however, say that a violation by a person in a particular case did not occur because the Constitution does not include a power to submit objects for inspection, hypothetically.

The Constitution, like the law itself, isn’t “flexible”; it isn’t alive. It doesn’t change with each new generation of political thinking, even if some new words come into vogue or others leave the vernacular. Does “No Parking” change in meaning because cars are smaller? Does a firearm change its lethality because we invent a new word to it label with?

Executive Power

Presidents and executive administration officials under him may not like that every single person entering the US must show valid identification papers or else be sequestered until a determination of identity can be made, but it is the law. I may not like being the one detained at the border crossing, but to ignore the law for expediency or to interpret the law according to an arbitrary set of rules that is not passed by the legislators is simply wrong.

NPRM (notice of proposed rule-making) is a prime example of how Congress is bypassed in its legislative role. Regulators call in industry and interested parties to determine what rules the agency will implement – no, Congress is not consulted. After the rules are published, they have the effect of law, but Congress never ratified them, and may not have even been aware of the process, at least until published in the Federal Register.

Executive Orders and Regulations

If only Congress can write the laws, how do we get regulations done? Not by Executive Orders and not by Administration-written Regulations. If the administration wants a particular wording for rules empowered by public law, then the administration must submit its proposed writings to Congress for approval. The Legislative branch needs to be in charge of the writings that make up our law. They must approve every teensy-weensy bit of writing that is law.

The Executive is restricted to Enforcing the Law as written by Congress, not as the President feels it should be.

If only Congress knows what they meant in writing a law, how do we get judicial decisions that conform to the law? Not by interpreting the written word of law according to a judge’s set of prejudices and beliefs. When a judge misinterprets the law, Congress needs to be able to correct that misdeed.

The Judiciary is restricted to deciding if a law was violated or not. It cannot un-write laws or re-write them to suit its political agenda.

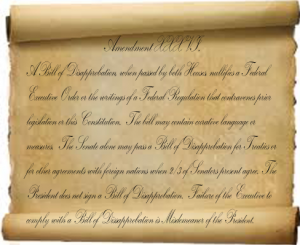

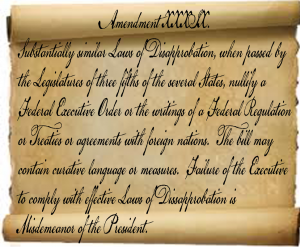

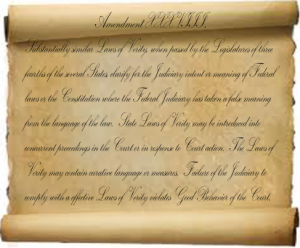

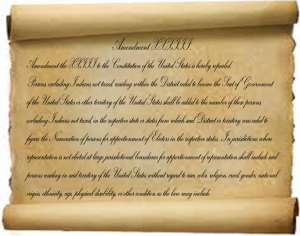

Amendment 36

In Congress’ Oversight Authority we discussed the need for oversight by Congress, our legislative branch, and Amendment XXXII was proposed to codify that role to limit the Executive from legislating. But if the President takes action via an Executive Order, we need a mechanism by which that Order can be disapproved, either by Congress. The several States need also to be empowered to exercise similar power over the Federal Executive, when a super-majority of States pass similar Bills of Disapprobation.

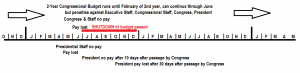

In neither case using Amendment 36 or 39 does the President sign or approve in any way the disapproval of what he has already done. Obviously, he would never approve of disapproval of his works. Note that the Senate alone may disapprove “deals” or what normally would be called a Treaty for Constitutional purposes.

In both Amendments the President by not complying with Disapprobation is conducting himself in Misdemeanor (as mentioned in the Constitution, grounds for Impeachment).

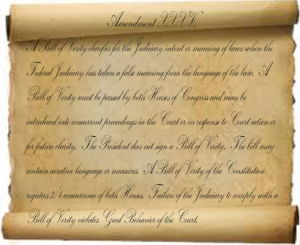

Amendment 35

The Amendments above might address and out-of-control Executive, but how can we rein in an out-of-control Judiciary? Similar to the Bill of Disapprobation, we can have a Constitutional clause by amendment to disapprove what the Court has ruled. We could also do that in advance if we’re worried they’ll misinterpret either a law or the Constitution itself.

A Bill of Verity is similar to amicus curiae only stronger in that it carries the Constitutional weight of directing and correcting the Judicial branch.

As with the Bill of Disapprobation, if the Judiciary ignores the Bill of Verity, they’re conducting themselves in Misdemeanor. Impeachment applies to Federal officials charged with High Crimes and Misdemeanors.

States also need the power to correct the Judicial branch in case they have overstepped their bounds. Amendment 38 provides a Constitutional mechanism for a super-majority of States to correct the Court on judicial matters, in effect to rein them in when necessary.

With the power of Congress to rein in the Executive or the Judiciary plus the power of States to do the same via Bills of Disapprobation and Bills of Verity, we can expect the Federal officials to behave themselves with respect to legislating from the bench or in the oval office.

The last piece of the puzzle is to rein in the power of Congress itself when the States have observed that Congress needs to be corrected or constrained. Term Limits may provide some fear factor, but we also need to power to recall and the power to disapprove Congressional actions from The People or the States.