Necessary Evil or Avoidable Punishment?

A short article on taxes

Supreme Court Justice Learned Hand in his famous Helvering v Gregory ruling said:

“Any one may so arrange his affairs that his taxes shall be as low as possible. He is not bound to choose that pattern which will best pay the Treasury. There is not even a patriotic duty to increase one’s taxes.”

In fact, many courts have tried to clarify that taxes are not something unavoidable, meaning we have the right to minimize them, avoiding them altogether if we legally can.

Does that mean that we should feel guilty about doing so, or should feel morally obligated to pay, even when we don’t have to?

Evading isn’t Avoiding Taxes

Here we’re not talking about evading taxes, meaning a justified levy for tax purposes that we simply figure we’re not going to pay because we don’t want to. We mean searching the rules laid down by the IRS or whoever is making the laws, regulations and rules to implement them simply to find a way to minimize what we legitimately obligated to pay. We also don’t mean taking illegal steps to evade paying taxes.

Changing your name to evade taxes obviously is wrong. You incurred the liability – just do what’s right and pay.

However, we’ve come to look at what other people do and ask why not apply the same rules to ourselves. My wallet contains my money, and I should be able to preserve it for what I want to spend it on or just save it to spend later. Right? That’s what freedom is about. Using your assets in the way you want (so long as nobody else has their equal right to do the same thing impinged upon by your so doing) is freedom.

Where do taxes come from, then? Why do we owe them? To whom are they actually owed? How do we collect them? How do we decide how much they are? Some say they’re punishment. In some ways they are.

Taxes for Streets and Highways

For example, if the average vehicle weighs 6,000 lbs and causes a certain amount of wear and tear on our roadways, then we can figure the cost per vehicle or per mile per vehicle to maintain the roadway(s).

But when some truck is allowed to share the road with the 6,000-lb cars and it weighs 80,000 lbs fully loaded, we can expect that the truck causes more wear and tear per vehicle-mile than the passenger cars. Yes, engineers studied this issue decades ago and revealed a few engineering facts to the public and to political decision-makers those facts were egregiously ignored.

For easy math, let’s say the truck is 10x heavier than the car. The engineers computed that the wear and tear was actually several thousand times greater. For you engineers out there, the math is related to strength of materials and does vary over temperature. Clearly, whether the truck is loaded, partially loaded or an empty tare also affects the answer. But, if the 9,000x greater damage caused by trucks is to be taken into account, shouldn’t the truck (when loaded) pay more to maintain the roadway than the passenger car?

The roadway may know the difference but only the government (the owner of the road) can assess the cost on the truck. We call this process of levying costs imposing taxes. Wait, you say. Don’t trucks get worse fuel mileage than cars, and in effect, don’t they pay more per mile than cars do? Well, 9,000x is a heck of lot more damage than 5 mpg versus 20 mpg. So, they’re buying 4x the fuel (laden with tax), but they’re burdening the road with 200x that in damage.

How do we recoup that cost? Taxes.

Of course, we could simply ignore the cost burden. Railroad companies spent mega-millions to improve their roadbeds, but unlike train trackbeds, the roadbeds (and surface) for highways and streets are not paid for by the company that owns them, because the company is the government. We own and pay for the roads.

We pay for their construction and for their maintenance through taxes. That system of tax collection and usage should be fair, easy to understand, and straight-forward to fund.

Fair doesn’t mean exactly equal, although some people believe things can’t be fair unless they’re equal. But, ask yourself how you would react to the following scenario.

Your HOA has a clubhouse that can be “rented” by the members (or others). The fee is fixed for any usage: no matter which day, what time, how large a group, or what happens to the facility. So, a small group comes almost a year in advance and reserves the clubhouse for New Year’s Eve to have a party. They carry on until the wee small hours of January 1 and leave an untidy mess inside.

Another larger group uses the clubhouse Wednesday afternoons to play bridge at their own card tables for a couple of hours and leaves the room immaculate. Should both groups pay exactly the same thing? Fairness comes into play, doesn’t it?

Some would argue that the large group should pay more because of the size of the group. Some would say the messy should be assessed a cleanup fee. Some would say the holiday rate should be higher than the non-weekend usage. And so on. The thinking here is somewhat obscured, but the large group does cause more wear and tear, the shorter time of use should be reflected in the wear and tear, and the demand for holiday usage costs other people the opportunity to use the facility equally. A profit-seeking firm would not pass up the opportunity to charge more for the holiday time with its higher demand.

We can’t capture all the relationships easily, but we can see the cleanup is a burden that the bridge group shouldn’t have to bear, can’t we? We can also see that the general members should not have to bear the cleanup cost either. If the bridge people do no harm, but the party people place a cost burden on the facility owned in common by the neighborhood, then clearly the fee for the party-goers is going to be much higher than the bridge-players. Goren would be pleased to hear that.

Moreover, demand on scarce items needs to be accounted for. If 20 families want to use the facility on New Year’s Eve, shouldn’t we let the one offering the most money pay, and then the whole neighborhood benefits by having their portion of the shared cost of clubhouse ownership reduced from the large payment of the highest net bid to use the facility. “Net” here means accounting for the damage and cleanup, etc. The other 19 families will have to look elsewhere to hold their party, but presumably they picked the clubhouse for its closeness and low price. So, another place will be priced to account for its closeness on better terms, or else those families would have bid more for the clubhouse. Trying to give “everyone” the “equal opportunity” to rent the clubhouse will result in lower revenue and thus higher cost to everybody but the member who wins the cheap rental.

Some would say that it’s not fair that the clubhouse be rented at the highest net revenue to the HOA. They would want the clubhouse available for free and then a lottery to decide who gets it. This isn’t the capitalist way, but it can be an acceptable way to do it. If you were one of the families, would you not be able to decide how much the party venue is worth to you? Would you be equally happy if a bunch of frat guys got the place and your family mini-reunion were displaced, simply because you lost the lottery? (You might even feel that someone cheated.)

Suppose your HOA had a Sales Manager reporting to the board. His job would be to maximum revenue for the association within the rules established for the clubhouse. He might allow free usage Tueday through Thursday for groups less than 10 for daytime use, and set a $20 price for non-holiday weekends. Maybe he would set a $50 fee until the day before the proposed use and then lower it to $25. His job is to bring in revenue so that your HOA fees go down. You want him to fill the clubhouse regularly and bring in paying customers, while keeping the cost down.

That’s government’s job, too. Bring in voluntary revenue to keep the cost down for the rest of us. But in a bureaucratic system the price would be fixed and not adjusted to sell the “empty seats” or account for low-cost usage. An airline, for example, offers seats to flyers at the last minute at much reduced pricing so they get something for the empty seat rather than nothing. A government body doesn’t think that way. They are not profit motivated, and therefore not about reducing the taxes they need to collect by generating extra income. Government simply doesn’t think in a way to minimize the cost burden to non-players. Non-players are the vast majority of people who just don’t ask for services, don’t laden the government with demands, and basically don’t do anything but pay for everybody else.

Getting back to the loaded tractor-trailer versus the passenger car, the government thinks in terms of axles, not damage to the road from weight, and in terms of fixed pricing, not about selling empty seats. A tollway, for example, that is well underutilized between 10 AM and 2 PM, could sell passage for reduced prices and bring in additional revenue (maybe). Alternatively, when tollways are nearly empty at 3 AM, the toll could be half or less to encourage drivers to get off the roadbed built for street traffic and travel the toll-paying highway to save time.

Tolls and Taxes

Both forms of collecting money are in use today. We tax the gasoline, we extract fixed tolls by axle from vehicles, and we don’t try to understand the market implications of these actions. Taxes on all vehicles raise their costs. A per vehicle tax is even worse. The vehicle could sit at home undriven for months and yet the government wants the owner to share in road costs – that’s wrong.

The truck usage increases road maintenance enormously, especially in colder weather, yet pays only slightly more than the cars to – that’s wrong, too. In effect, the taxes punish everybody who owns a vehicle or who drives one, but heavier and more effectively utilized vehicles pay a disproportionately lower share of costs. The punishment is not according to the crime. Tolls by axle are even more ridiculously imbalanced and favor huge vehicles. Why should a 4-axle truck pay only double what a 2-axle passenger car pays, in light of the wear and tear caused?

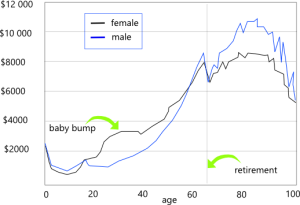

The same principle applies to government levies in general. Why should the couple in their 30s pay taxes equal to the family of 5 in their 30s? Why should the 50-year old doctor pay taxes equal to the 25-year old single guy working in a restaurant and living at home? Why should be low-income single mother pay more or pay less than anyone else?

The principle of punishment for burdening the rest of us should come into play. Government isn’t about equality of payment, and fairness is in the eye of the beholder. A female who spends 12 years getting her medical degree and internship to become a well-paid doctor is somehow placed in the same bin with a used car salesman making the same money. Is that fair? A day laborer, a doctor, an engineer, a call-center representative – should they all be taxed the same? The same in what way? The same percentage? The exact dollar amount?

Should we look at the total bill that has to be paid and then divide it up evenly for all of them? Should we punish the doctor for not contributing all those years into the tax coffers? Should we punish the day laborer for not getting a job that adds more value to society? Should we punish the engineer for making a good salary? Should we punish the CSR for participating in an enterprise we all find frustrating? After all, taxes take away money from people.

Maybe the bills the government pay are just a necessary expense and we need to collect tax any way we can to pay them, regardless of how it affects short- or long-term actions. If everyone knows that doctors pay more in taxes, then maybe there will be fewer doctors. Or, if day laborers pay the same tax as CSRs and engineers, then maybe everybody will look for a way to earn more money to pay for a tax that is evenly split for everybody.

Some would argue that the day laborer just doesn’t make enough money to pay the tax and the doctor makes so much more than he needs. So we have all swallowed the “progressive” tax dogma that people who earn more money should pay a higher percentage of that money they earn than those who earn less. They even call it “progressive” as if anything else would not cause progress. And they call a straight percentage tax “regressive” as if it would take us back to some horrible past time where dinosaurs rule.

The Disconnectedness of Taxes

The heart of the problem is budgeting. When you or I plan on spending for some large ticket item, maybe a new car, maybe a flatscreen TV, maybe a new house, we sit down and figure out how much we can afford.

If the numbers indicate we can’t afford to buy it now, we save up and come back when we can pay more down and carry a smaller balance. We know our income is connected to what we spend. We budget. If we don’t make enough, we plan on how we can get a little more training and get a higher paying job. We can also use some of our free time to work at a second job. The additional income may be enough to cover a short term gap so we can get the item we’re craving or just plain need to have.

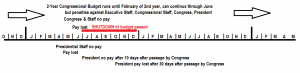

Government doesn’t think this way. The spending budget isn’t really a budget – it’s a plan to spend. Income is an afterthought. If the government doesn’t bring in enough revenue, then it first borrows the shortfall (which we sometimes do on our credit cards, if it’s temporary) and then because each purchase or program is not tied to a particular revenue stream, they have to increase some tax somewhere to make up the shortfall. But, usually they wait until it’s a crisis of some sort, and claim that some other “budgeted” item has to be scrapped because not enough taxes were paid in.

Robbin’ the Hood

This is a lot like the sheriff of Nottingham sending his tax guys out again to collect more money when the sheriff overspends.

So, how is a tax collection punishment?

The sheriff of Nottingham doesn’t look at the second tax collection as punishment – it’s just a necessary action. The fact that the sheriff’s peasants don’t have enough money to buy flour to bake bread or can’t feed their children doesn’t seem like punishment to the sheriff. That deprivation is a price we all have to pay to belong to a fair and equal society, right?

We all know it’s the fat cats are at fault for the deprivation, right? Those lords and ladies who live it up in the castle off the food stolen off the peasants’ tables are to blame. Probably you’re right that the other people in the sheriff’s castle are benefiting from the burden of taxes. But is it the guy who sells his vegetables in the market who benefits? No, we know he can’t be a fat cat because he has to pay taxes just like the rest of us, but at least he can afford it.

He will afford it as long as he doesn’t get so discouraged by working his butt off and giving most of it to the sheriff. At some point, though, he will simply move to Scotland. Then the number of stalls in the market will be fewer and filled with less and less. The sheriff will step forward and accuse those market-creators who headed north of not playing fair. Others will accuse the departed small business owner of being in the 1% and not helping the 99% by sacrificing more.

Who are the 1% – fat cats?

Perhaps then you’ll think that the fat cats are actually the people in the castle – the sheriff’s men. The sheriff, however, collaborates with other powerful people, like neighboring dukes, barons and other nobility. He also cooperates with powerful church leaders, who are tax-exempt. So, where are the big, multi-national corporations? Back in the sheriff’s time, only the Catholic church would qualify for that title. Imperial governments might be classified the same way if they were large enough. The Ottomans ran such a huge empire.

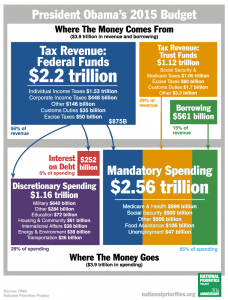

Back to present day. We know the Federal government, and each of the state and local governments don’t consider taxes a punishment nor do they think that anyone is being deprived by paying taxes. Some figures might help clarify the truth of it.

Medicare collects 2.9% of your paycheck. In addition, the Social Security Administration also collects 15.3% of your paycheck. That 18.2% sum is evenly split between you and your employer. Your employer coughs up the same amount you do. When you get a salary of $50,000, the government is receiving $4,550 out of your paycheck plus another $4,550 directly from your boss. Your $50,000 salary actually costs $54,550 when the Federal Medicare and Social Security taxes are included.

You’re the Fat Cat – that the government wants to tax

If you could put away 18.2% of your wages or salary every year consistently for 40 years, you’d be a fat cat yourself. Imagine there were zero inflation and that your paycheck remained constant forever. At the end of 40 years you would have donated 728% of your annual earnings. For a $50,000 earner that’s $364,000 in the bank.

Of course, money in the bank always earns a little interest, maybe 1-3% per year (net of inflation). No, we’re not talking about stock market growth or real estate bubbles – just normal real returns after accounting for consumer price inflation. Your $364,000 with the actual net interest would be around $560k.

That’s like having 16 years of salary coming in if you stopped working. Huh? $560,651 accumulated after 40 years of putting aside $9,100 a year and earning 2% interest per year with zero inflation means you lived on $40,900 a year and $560/41 leaves about 16.2 years to receive the same income when the interest it will earn while being depleted is counted.

Where is my retirement?

So, if the government “saves” 18.2% of your salary every year (and assuming there is no government-induced inflation), then after 40 years your account balance should have over half a million dollars in it. If the government is holding $560k for me, where is it? I earned $50k a year and lived on only $41k of that. Do I now have an account with money in it or not? No. Social Security is not an individual account with a balance in it that you can transfer or roll over into a stock portfolio or purchase a real estate with. In fact, the aggregate account where everybody’s money is held is actually empty.

The government pretends that it’s holding the money and pays you with money it receives from others paying into their “accounts” in a large Ponzi scheme. Ponzi convinced people he was getting fantastic returns by paying huge dividends on investments he received by taking money from new investors and giving to the old ones, telling them they had 20% returns in only 30 days. Of course, the winners told their friends, who told their friends, and they was a huge influx of new investors with large returns also. But the whole time the original investment money was gone.

Ponzi spent what he didn’t return to old investors as if the money were his own. His lavish lifestyle came to a crash when investors wanted the actual money, not just a statement saying they were rich. If the number of withdrawing investors was small, they might feel foolish that they weren’t patient (but of course they did live well on the proceeds). As the number of withdrawing investors grew, the problem suddenly became apparent: there was no money in the bank with their name on it.

In Social Security the number of withdrawing investors is about half of the new investors. Decades ago the withdrawing investors were only a few percentage points of the total. The problem has now come home to roost. Who will rescue this Ponzi scheme?